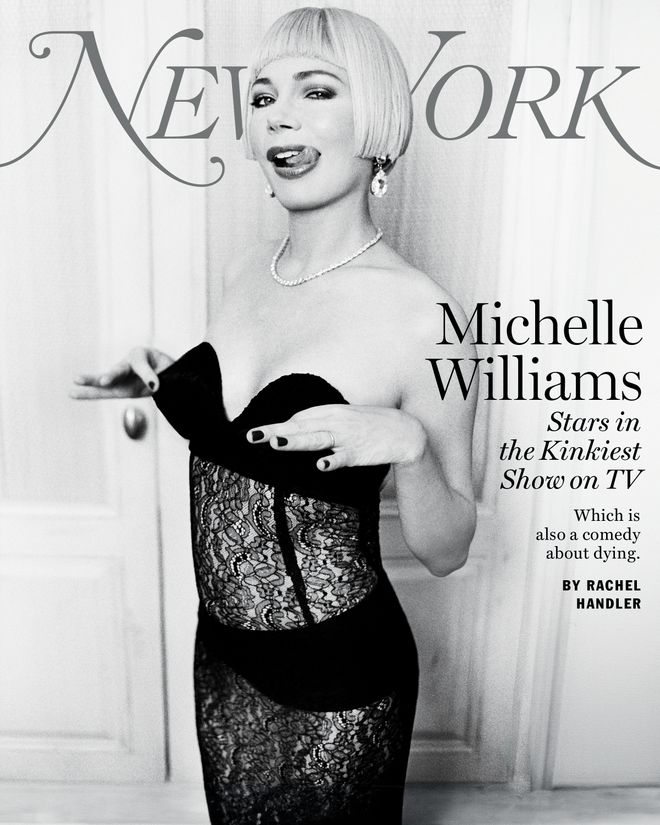

Full look by BALENCIAGA. Earrings are stylist’s own.

Photo: Ellen von Unwerth

Michelle Williams was winding up to kick Rob Delaney in the dick. They were on a soundstage in Brooklyn decorated to look like a typical New York apartment, both grinning and audibly panting. Williams was fully clothed, wrapped in a scarf and sweater; Delaney was wearing only underwear and what he describes as a “fascinating harness” — a protective bowl of sorts, “invented by some sicko” — that sat “eight or nine inches below my real gear.” Though Delaney was more physically exposed and in more imminent bodily danger, Williams had the more difficult emotional task: playing a woman who is just now, in her 40s, figuring out that she likes to dominate men and is simultaneously horrified, delighted, and confused by the sheer fact of her desire as well as by the idea that she is allowed to act upon it. Oh, and this woman is on the verge of death. Also, this is based on a true story. And it’s a comedy.

“I want to hit you and kick you in the dick and destroy you,” said Williams, spitting out her lines like bad coffee. “Do it,” said Delaney, eyes wild with lust, miming masturbation. “Kick me in the dick. Please.” Her face was an amalgam of horny disbelief and disgust. She backed up to kick him, connected hard. The “kick-in-the-nuts approximator,” as Delaney describes it, was close enough to his testicles that he could feel her hitting it in real time and react appropriately. Both fell to the floor — Delaney groaning in ecstasy, Williams screaming in agony. Her character, a stage-four breast-cancer patient, has snapped a bone in her leg and needs to be rushed to the hospital.

They shot the scene over and over for half a day, which meant at least “nine or ten kicks to the nuts,” Delaney says. “We rode the hell out of that thing.” Williams remembers the day as “nerve-racking.” “But I don’t think I hurt him,” she adds.

Nearly every moment of Dying for Sex — an FX limited series based on the hit 2020 podcast of the same name, itself based on the life of Molly Kochan, who hosted the podcast with her best friend, Nikki Boyer — feels both funny and shattering. The eight-episode show, premiering April 4, kicks off at a couples-therapy session during which Williams’s smart, put-together, and deeply sexually repressed Molly gets a call from her doctor with a terminal diagnosis. She stands up, immediately leaves the session and her mediocre husband (Jay Duplass, perfectly condescending), meets up with Nikki (a transcendent Jenny Slate), tells her she’s going to die, and later asks Nikki if she can “die with her” instead of within the claustrophobic confines of her marriage. Nikki absorbs and accepts the proposal, and while under her care, Molly embarks upon a frantic sex quest with the express goal of figuring out what actually turns her on — and if she can orgasm with another person — before she dies.

Co-creators and co-showrunners Liz Meriwether and Kim Rosenstock met working in theater in New York in the early aughts and went on to collaborate on Meriwether’s long-running hit sitcom New Girl. Rosenstock started writing the Dying for Sex pilot a few months after COVID hit. It was all as heavy as you may imagine. “It asked me to reckon with my own mortality and think about the kind of life I wanted for my daughter and the relationship I wanted her to have with her body,” recalls Rosenstock. They had no direct points of comparison narratively or tonally (though they kept thinking about the ruthlessly honest, bleakly funny I May Destroy You and the hot, realistic sex in Normal People). They had no idea if what they were doing would translate to FX execs or to an audience or even if they could make something they thought was good. “We would kind of all look around at each other and be like, ‘Is this okay?’” says Rosenstock. “‘I think so. Let’s hope so. Let’s just keep going.’”

“The show careened from dramatic to absurd to hilarious to unbelievable and then back again. I was just sort of wondering what the tone would be. And nobody gave me an answer,” Williams says, laughing. It’s late February, and we’re wedged into a corner at Inga’s Bar, one of her favorite restaurants near her Brooklyn Heights home, where she asks to meet for both of our conversations and where nobody really seems to recognize her, though we do bump into Alison Roman wearing her new baby. (Williams recommends a butt salve — “not for adults.”) Williams and Meriwether are identically dressed in white sweaters and jeans. They both want to order something called “tender lettuces,” which we all agree is thematically resonant. The show could only have starred Williams, Meriwether says: “We needed the Simone Biles of acting.”

Dying for Sex comes at a fascinating time. We’re living under an openly fascisticgovernment whose express goal is to wrench any remaining agency, sexual or otherwise, from anyone who is not a white man with an upsetting hairline. Yet we’re suddenly surrounded by stories, fictional or otherwise, about women over 40 fucking their way to self-actualization: Miranda July’s All Fours, the Nicole Kidman–led MILF renaissance, a deluge of pro-divorce memoirs, a recent New York Times Magazine piece about how Gen-X women are having better sex than anyone else. On paper, Dying for Sex shouldn’t work as well as it does, rife as it is with opportunities for maudlin sentimentality. But Meriwether and Rosenstock have managed to make something truly novel. It’s casually groundbreaking in its treatment of heterosexual sex; its protagonist has sex with multiple men largely without vaginal penetration, a choice that stands in direct opposition to most of the show’s thrust-loving American television forebears. It explores kink as an opportunity for liberation and catharsis,not as a punch line or dark Freudian detour on the way to conventional sex. It doesn’t shy from the visceral realities of what happens to a human being as she dies — the sounds, the way time slows and distorts. It’s proudly weird and theatrical, featuring a hallucinatory dream-ballet sequence complete with custom puppets, one of which is a hyperrealistic penis outfitted with fairy wings.

“It definitely opened my eyes in a way that was also like, God, I’m such a dummy for not having realized this stuff sooner,” Williams says about how the show influenced her feelings about sex. “There was something about Molly choosing to continue to feel, and how painful that choice is — to feel things when you know you’re not going to be able to feel for much longer,” adds Meriwether. “I think about that a lot.”

“That’s why sex is an answer to death. Because it’s the ultimate feeling before we’re left without any,” says Williams. She jokingly slaps the table for emphasis. “I got to go home and see my husband!” she says, laughing as she stands up.

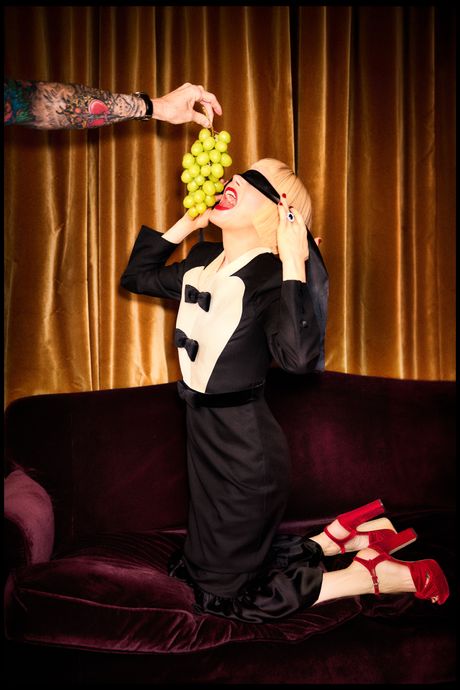

Dress by DOLCE & GABBANA. Necklace by DORSEY. Earrings are stylist’s own.

Photo: Ellen von Unwerth

Williams, who has been working consistently since she paddled into Dawson’s Creek at age 16, has long proved her ability to play women navigating all manner of existential and literal crises; she has had far fewer opportunities to be funny. Her comedic turns — such as in the underrated ’90s Watergate satire Dick — were memorable enough that Meriwether and Rosenstock knew she could handle the show’s slapstick physicality, the endless quips, the tonal whiplash. Plus Williams looks uncannily like Kochan, especially during Kochan’s final years: short blonde hair, model bone structure, expressive eyes.

Williams, Meriwether, and Rosenstock all Zoomed in 2022. Before they spoke, Williams, who had most recently worked on The Fabelmans, had listened to the podcast, which Boyer and Kochan recorded together from the beginning of Kochan’s sexual escapades through her final months. It moves from the two giggling and gossiping about Kochan peeing in a man’s mouth or giving a surreptitious hospital-bed blowjob to something more profound with Kochan reflecting on her changing relationship to herself, her sexuality, her mother, and her childhood sexual trauma, all while coming to terms with her mortality. “It destroyed me,” Williams says of the podcast. “It’s not often that you get such a strong emotional reaction. You like things, you can admire things, you can be provoked by things. But to be just obliterated by something? I can’t know when I last had that experience.” She “cried and blubbered” after listening to it, then listened to it again. “I was like, What just happened to me? Things don’t usually get to me like that. And I was like, I need to respect the fact that something in me that I’m not really capable of verbalizing at the moment is drawn to something in this.” When I ask her to name what exactly she couldn’t shake, she thinks for at least a minute. “It’s human bravery,” she says finally. “I think that’s the thing that gets me about it. Bravery, in the midst of the most impossible circumstances, to do something your own way.”

She didn’t sign on immediately — originally, the show was set in Los Angeles, which would have meant a temporary move. “When you have small children, you become thoughtful about the time you spend away from them. And so I don’t work a ton, but I still want to work,” Williams says. She agreed to read the next few scripts when they were ready. “It wasn’t necessarily the thing that I saw myself doing. I’m a mom. I got all these kids,” she admits, spearing a tender lettuce. “I’m going to go do a show about what?”

Then she got pregnant. She stepped back from the project in 2022, had her third child, and recorded the audiobook for Britney Spears’s The Woman in Me. In the meantime, Meriwether and Rosenstock continued to work with a writers’ room comprised of five women, one nonbinary person, and one man and wrote the next few episodes. When they emerged 20 weeks later, they set out to get Williams again. “She’s our dream,” says Meriwether. “And we were like, ‘How do we get our dream back?’”

Early the next year, Meriwether ran into Williams at the 2023 Critics Choice Awards. Williams was with her best friend, Busy Philipps, whom Meriwether also knew. She anxiously approached them, telling Williams, “I’m moving to New York, and I would still love for you to do this. We have more scripts.” Williams thought about it. She hadn’t worked in a while and was getting the itch. “I was like, I know I had a baby, but two and a half years is retired,” she says. “This is getting crazy.” Her eldest, Matilda, was obsessed with New Girl (“We kind of raised her together,” she jokes to Meriwether) and really wanted her to do it. “To go make a show about sex and death with so many unknown elements, you really do need the support of your home team to say, ‘Go, Mom, go,’” Williams says.

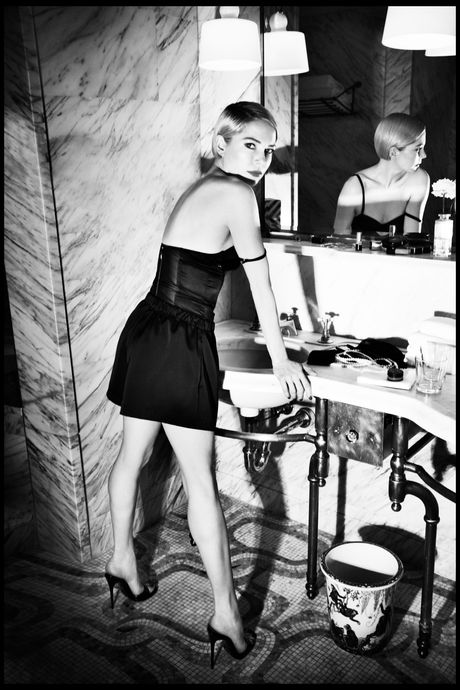

From left: Dress by VALENTINO, shoes by JIMMY CHOO, and ring by DORSEYbodysuit by FLEUR DU MAL, shorts by LESET, and shoes by MAISON ERNEST

From top: Dress by VALENTINO, shoes by JIMMY CHOO, and ring by DORSEYbodysuit by FLEUR DU MAL, shorts by LESET, and shoes by MAISON ERNEST

A year and change later, Williams was trying to figure out how to fake an orgasm six different ways. It was one of her first days on the Dying for Sex set, and she was filming a scene in which, just after Molly leaves her husband, she gets a hotel room and a vibrator and masturbates for an entire day in an attempt to figure out what turns her on, eventually dumping the overheated vibrator into an ice bucket. “You’ve already done, like, four scenes, and then it’s five o’clock at night and you have to do six masturbation sequences with six sculpted, individuated orgasms,” recalls Williams wryly. “And you’re like, ‘Woo! Okay.’” Meriwether, Rosenstock, and the intimacy coordinator were standing by on set to offer notes. “We talked about how realistic each orgasm was,” says Meriwether. “How one should sneak up on you, how the last should be like finishing a marathon.” Williams was game but nervous. “I just kept joking, like, ‘Just so you know, this is how Molly comes, not Michelle,’” says Williams. “This is not my come face.”

In Montana, where Williams grew up, her own sex education was nearly nonexistent. “We were given a tiny bottle of Clearasil for our acne and then told how to put a condom on. That was puberty. Sex can kill you or make you pregnant. No one ever talked about pleasure,” she says. “I think I still struggle with it. I’m still a little embarrassed about it or not sure how to talk about it.” Meriwether and Rosenstock invited Emily Nagoski, the writer of Come As You Are, a book about female desire, to speak to the writers’ room. “In her book, she talks about the No. 1 question she gets asked: ‘Am I normal?’” says Meriwether. “I don’t know if it’s an American thing or not, but I just think that’s this deep fear for so many people, and there’s so much shame here around it.” Kochan, alternatively, “was this force of acceptance” around sex, adds Meriwether.

On the show, Molly tries everything she can think of to get herself off: chatting with a cam-boy, watching the scene from Speed when Sandra Bullock gets to drive the bus, observing clown fish going in and out of a coral reef. The last was related to a New York Times article Williams read about how women, uniquely, can be turned on by almost anything. Meriwether, Rosenstock, and Williams were all riveted by the way Kochan discovered exactly what brought her pleasure. The show expresses this via Molly’s slow opening to various types of sex and intimacy but also via Sonya, her queer, sex-positive palliative-care social worker played with charisma and empathy by Esco Jouléy. Sonya becomes a sort of kink doula for Molly, easing her into new notions of eroticism. During one conversation from her hospital bed, Molly laments to Sonya that she “can’t even have normal orgasms from normal sex” and then says, “I made my neighbor jerk off in front of me while I said truly horrible things about his penis and then I kicked him in the dick. I loved it,” sounding despondent. “I don’t want to have to hurt people to have orgasms. What’s wrong with me?”

Sonya laughs. “Nothing the fuck is wrong with you. You early millennials are so tragic. You think sex is just penetration and orgasms. Why? Because that’s what Samantha said? Sex is a wave. Sex is a mind-set,” Sonya says. Molly is rapt. “Here’s the thing about your body,” Sonya concludes. “You have to listen to it. Yes, maybe it’s saying something you don’t want or you don’t understand. But give it a chance and listen to it.” Shortly after, Sonya brings Molly to a kink-forward “sex-party potluck,” where Molly is entranced by the possibilities of BDSM. Her eyes widen as she watches a live domination-and-submission scene. “That’s what I want,” Molly whispers.

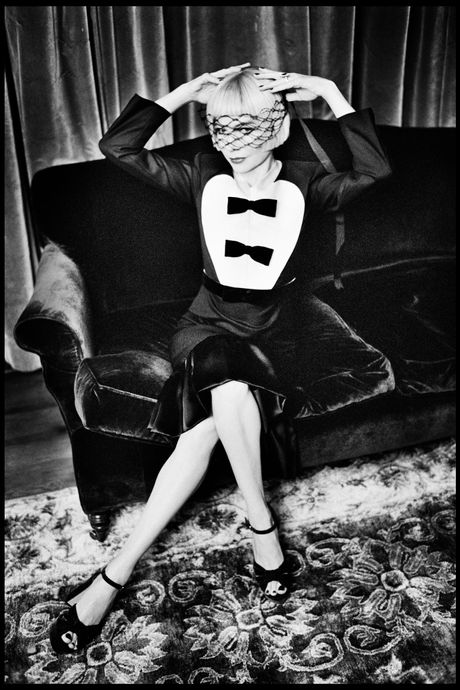

From left: Dress by VALENTINO, shoes by JIMMY CHOO, and ring by DORSEYfull look by BALENCIAGA and earrings are stylist’s own

From top: Dress by VALENTINO, shoes by JIMMY CHOO, and ring by DORSEYfull look by BALENCIAGA and earrings are stylist’s own

Meriwether, Rosenstock, and director Shannon Murphy wanted to avoid the pitfalls of Fifty Shades of Grey–type movie sex, in which everyone is clean and hairless and often being manipulated into doing things like having a spoonful of ice cream fed into their vagina. Dying for Sex features scenes of joyful BDSM negotiation — in one scene, over coffee, a chipper finance bro asks Molly if she’s “into cock cages” as he outlines his own boundaries. “So when did you figure out that you liked orgasm torture?” asks Molly. “Probably when I was canvassing for Obama,” he replies. “No bruises. I work in finance. But I do want you to step on me, and I’m into penis humiliation.” Williams is never nude onscreen, something they all agreed upon as a choice that felt natural; in real life, Kochan often wore a bra during sex. (There is, however, a delightful preponderance of dicks on the series, so many that FX asked them at one point to pull back on the male full-frontal just slightly.) Their primary goal was to make sure the joke is never on the person or the sexual act itself, to make it all feel real while being genuinely funny. Whereas on other shows, like Industry or Sex and the City, peeing on someone as a form of kink is used to implicitly make fun of or pathologize the character, on Dying for Sex, it’s presented as playful, an opportunity for sexual creativity. Molly invites a man dressed as a puppy to her apartment, gamely brings him into the bathtub, and straddles cheerfully over his face to pee on him. Later, he marvels at her sexual improvisational skills: “I’ve never had someone check me for ticks before. How did you think of that?”

A week later, I’m sitting in another restaurant across the country, this time with the real-life Nikki Boyer. We’re at Hugo’s in Studio City, Los Angeles, the last place she ever ate lunch with Kochan. This week marks the sixth anniversary of Kochan’s death, and as Boyer recalls their decadeslong friendship, she cries often, easily, and unself-consciously, without apologizing or really even acknowledging it. “Sometimes I feel like I’m talking for her and I’m trying to make sense of her. I think I’m probably the best person to do it, but still,” she says. “Maybe she’d be like, ‘No, bitch, that is not what I …’” She pauses and shakes her head. “No. I think she’d be like, ‘That’s okay. That’s not really what I think, but that’s okay. I love you anyway.’” She twists a ring around her finger. “This is her ring I’m wearing.”

Kochan, then 26, and Boyer, then 24, met in an acting class in Los Angeles in 1999. They didn’t warm to each other right away. Kochan was envious of Boyer, a St. Louis transplant who was boisterous, flirty, and determined to use the class as an opportunity to network and eventually make a name for herself as an actor. Kochan, who’d moved to L.A. from New York somewhat recently, saw acting as more of a hobby; she wanted to make her mark on the world in some way, maybe through writing, but didn’t quite know how. Boyer thought Kochan was quiet and reserved but intriguing. “There was something about her long brown hair and her crystal-blue eyes,” she says. “I used to call her an alien model because she just has such a cool, interesting face.” They were paired for a scene study and eventually became best friends, spending the next several years having six-hour lunches, watching movies, and telling each other their deepest secrets. Their friendship was instantaneously intimate, emotionally and physically. Kochan, who ultimately had to get a bilateral mastectomy, used Boyer’s boobs as the model for her own reconstructive surgery. In a scene from Dying for Sex that Boyer says came from real life, Molly casually holds Nikki’s breasts as they chat in bed, describing them lovingly as a “cup of hot tea.” In the early years of their friendship, Kochan, who Boyer thinks was living off a bit of family money and wasn’t working full time, would ask to accompany Boyer on errands and to auditions, help her run lines, prep for jobs, and go with her to pick up family members at the airport. “She was such a great participant in life. She was like, ‘I just want to be with you,’” says Boyer.

In 2005, Kochan noticed a small lump in her breast and asked her OB/GYN about it. He dismissed her, telling her it was nothing and that she was too young to worry about cancer. She felt embarrassed for bringing it up. Six years later, the lump had grown big enough for her to ask another doctor about it. By then, the cancer had spread beyond her breasts to her lymph nodes. She underwent chemo, a bilateral mastectomy, radiation, and later breast reconstruction, and she began hormone therapy, all while trying to carry on as normal a personal life as possible. The hormones pumping into her made her as horny as a teenager, but her husband struggled to see her as a sexual being now that she was sick. They went to therapy and tried to figure it out. Then, in 2015, her hip started hurting — the cancer had returned, this time in her bones, liver, and brain. Her doctor told her she was going to die. About a month later, she began having cybersex with strangers.

Kochan bought sexy lingerie, snapped nudes, sent graphic sexts across international lines. She couldn’t quite explain what she was doing or why she was doing it, at first. But it filled her with purpose and pleasure, a new sense of herself. Within a year, she had left her husband. “I love my husband, but we weren’t really a romantic fit,” she explains on an early episode of the Dying for Sex podcast. “I don’t think that I can self-realize in the context of this marriage for many reasons — so I left.” Kochan quickly transferred her sexual adventures from the digital realm into the physical. She was open to trying anything: tickling, foot fetishes, domination, and going to a man’s house to have sex in the morning on a weekday. The sex was unlike any she’d ever had. In Screw Cancer: Becoming Whole, her posthumous memoir, which Boyer self-published, she writes about how penetrative vaginal sex had, throughout her life, been “an easy way to disconnect,” that the “intimacy felt like less than making out on a couch.” A combination of the meds she was taking for her cancer, which sent her into medical menopause, plus a negative sexual encounter on one of her early dates, meant penetrative sex was off the table entirely for most of her post-marriage sex life. She told Boyer about what she was doing early on, and Boyer was impressed and inspired. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is so fun,’” remembers Boyer. One of her only real moments of judgment involved the prebreakfast dates: “I’m like, ‘Who has sex at 9 a.m.?’” The two had always wanted to do something creative together, and Boyer came up with a name and the concept while they were driving one afternoon around the corner from Hugo’s. “I’m like, ‘I think your journey is a story, and I think it’s called Dying for Sex,’” she says. “So then her sexual escapades became a check-in with me: ‘I’ve got to tell you what happened.’ And we put it under this guise of ‘We’re working.’ We had this fire under us.”

Kochan and Boyer, who had by then had a few acting and hosting gigs, pitched it as a TV show first, but nobody bit. TV execs didn’t understand it or know how to package it. One suggested a “sexy, fun girl” Sex and the City–type thing. Kochan turned it down; she knew it needed to be more than that. She and Boyer eventually decided to start recording it as a podcast on their own, and in 2018, they produced a ten-episode show all about Kochan’s death-defying sexcapades.

Nikki Boyer and Molly Kochan in October 2015. Jenny Slate and Michelle Williams in Dying for Sex. Photo: Nikki Boyer; FX.

Nikki Boyer and Molly Kochan in October 2015. Jenny Slate and Michelle Williams in Dying for Sex. Photo: Nikki Boyer; FX.

Over the course of the podcast, Kochan, who was a magnetic, funny speaker with a rich sense of the absurd, dryly recalls “stepping on a guy’s nuts” and speaks with casual detachment about how she had to check with her physician’s assistant if peeing in a guy’s mouth could poison him because of the cancer drugs she was taking. But the reality of her health intrudes at inopportune times. She and Boyer recorded part of episode four, for example, from the emergency room, where she had just been admitted for blood clots; she bemoans her “fat leg.” Increasingly exhausted from the cancer and the treatments, she soon realizes the sex may not be working the same as it was before. “I was bummed out,” she says of this realization, “but maybe I’m evolving.” She shares with Boyer, quite vulnerably, that she might be interested in meeting somebody who can actually invest in love, somebody who wants to “learn me.”

By the fall of 2018, Kochan’s health was taking a serious turn for the worse. At their final lunch at Hugo’s, Boyer recalls her being weak, unable to keep food down. But both still thought she had years left, not months. About a month later, Kochan was hospitalized. Boyer became one of her full-time caretakers: washing her face, massaging her legs, bringing her soup, sitting with her as she writhed in pain. From the hospital, Kochan continued writing a memoir detailing the darker parts of her life, including instances of childhood neglect and sexual abuse that she says caused her to repress her sexuality and dissociate from herself. The memoir runs directly perpendicular to the podcast in tone — it’s raw, often angry, unvarnished. “I think the book was the wounded parts of her,” says Boyer. “I think the podcast was the truest version of her. And then, when I see Michelle play her, that’s how Molly would love to be seen.”

Boyer recalls sitting in her car alone in January 2019, acknowledging that Kochan was soon going to die. She was desperate to get Kochan’s story out before that happened, whether she had to release the episodes herself on YouTube or find a third party to assist her. Boyer had previously emailed Hernan Lopez, the then-CEO of Wondery, with a pitch for the podcast; he hadn’t gotten back to her, but she tried him one more time. As it turns out, he’d missed the first email and was walloped by the ten episodes she sent him. He came to visit Kochan at the hospital on Valentine’s Day, held her hand, and told her he was going to help tell her story. They started signing contracts while she lay in her hospital bed. In her last few weeks, Kochan was, as Boyer puts it, “unlinking from the world.” She began hallucinating — clocks flying off the walls, alien figures standing behind her doctors, feeding them information. “She was detaching from her body. I could see it in her eyes. I could see it in the way she looked at me,” says Boyer. But Kochan kept writing her book, and the two kept recording, though infrequently, on Boyer’s phone.

Boyer recalls how, during this time, Kochan was managing her death with confidence and a sense of control born from the way she had directed her sex life. She started turning down visitors who would drain her energy. She would directly address doctors who condescended to her or didn’t speak to her with enough humanity. She began thoughtfully giving away her things to the people she knew would appreciate them most. “She was so mindful of how she was going to spend her last days that I was like, ‘I think this is about more than just sex. This is about navigating your own ending and being really present for whatever life you have left,’” says Boyer.

The episodes from this time are wrenching to listen to. Kochan’s voice gets smaller, quieter, her breaths raspier. She lets go of the sex. “I don’t miss it,” she says. “Sex is great to plug you into your body, or to find your body, and I don’t need that anymore. My body did a really good job.” Kochan died on March 8, 2019, at age 45. She left Boyer everything: her memoir, her laptop, her phone. “She said, ‘Promise me that you’ll publish my book. Promise me that you’ll do whatever you can to get this out here.’ She very much wanted to make her mark on this world,” Boyer says.

Released in February 2020, about a year after Kochan’s death, the podcast is a combination of those ten original self-made episodes, Boyer’s in-hospital recordings, Kochan’s book, and the ruminating and reporting Boyer did after Kochan’s death. It was an instant hit. It made its way to Meriwether’s inbox that March via a producer she’d worked with who thought she’d be interested in it. At the time, Meriwether was in the middle of making the Elizabeth Holmes miniseries The Dropout, but she was immediately struck by Kochan’s story. “That podcast starts, and it’s like you’re just hanging out with friends,” she says. “And then by the end, you’re just like, How did this get to be the most profound story I’ve heard? ” Boyer had multiple meetings with prospective adapters before the final podcast episode aired. She asked Kochan for guidance when trying to figure out who would be the right person to tell their shared story. “I talk to her a lot,” Boyer says. “And the funny thing is she always said to me, ‘You’re my soul mate.’ And I would always be like, ‘I love you so much. No, you’re not my soul mate. Stop being weird.’ And now I’m like, Oh my God. She’s my soul mate.”

On the TV show, Jenny Slate’s Nikki runs herself into the ground, giving up nearly everything in her own life to take care of Molly, but she never lets her friend see the strain. Slate’s beautifully expressive face holds all of that in every scene: the immense stress she’s under, the deep pain she feels about her friend’s imminent death, the joy she gets from taking care of her, the rage she feels against the medical system that failed her, the cheerful veneer she paints on top of it all so that Molly feels supported and unafraid. In one memorable scene, after Molly nearly dies and has to have a breathing tube inserted, Nikki, going on 30-plus hours without sleep, stands at the foot of Molly’s bed and performs a series of monologues — Shakespeare, Cher from Clueless — while Molly, unable to speak, simply watches, radiating with appreciation and love.

When the chemistry read came Slate’s way in late 2023, she had long been looking for something with depth and breadth where she wouldn’t just be relying on her comedy chops. She had recently told her agents she wanted to wait for it at the expense of other jobs, which was particularly scary with a mortgage and a young child. “I kept saying, ‘I want to go full wingspan,’” Slate says. “‘I feel like I’m just being given little carrier-pigeon things. I want to do what I know I can do, but it’s hard to describe what I can do unless I can do it.’” When she got the role, Slate sobbed with gratitude. She says it feels like “the most important one yet.”

When it came to portraying Boyer, Slate didn’t feel she needed to mimic her. “I really only listened to the full podcast when we were almost ending because I don’t want to get in my head about not replicating her, and she doesn’t seem to care about that,” she says. “She cares about the spirit of the thing because she and Molly are spirit partners.”

When Boyer saw Slate and Williams on set and in character for the first time, she says, “it didn’t feel like me and Molly, but at the same time, it felt like me and Molly.” Williams’s transformation was particularly overwhelming to witness. “I think there was something spiritual happening because she morphed into Molly so many times where I was like, How would she have known that’s what she did with her mouth? How would she have known that’s how she held her shoulders? ” says Boyer.

Williams says she got her clues about Molly’s physicality from photos, the podcast, and her writing. “You can take a best guess, based on the available information, how they might move. She comes through so beautifully in the podcast, just her timing, her delivery,” she says.

Williams carried a notebook with her on set. “It’s my little school notebook,” she says, “my touchstones.” On every job since Blue Valentine, Williams says she has put together a character workbook full of ideas, inspirations, poems, quotes from friends, and stray notes about the world around her. It’s always a specific brand — Postalco, based in Japan — and has to have a grid pattern. “If something’s running dry,” she says, “I’ll just go back to my book and see if I can find something there that will freshen the scene up.” She keeps the details of the notebook to herself. “My own history that I bring to it, how the script wove with that, and how the words kind of become sutures for what I need to learn and how I need to grow” are things she guards protectively, she says. “You have to build some kind of safe place inside yourself. Otherwise you won’t last.”

There’s a beautiful photo of Susan Sontag taken by her partner, Annie Leibovitz, in 1998 at Mount Sinai Hospital. Lying sick in bed in a medical gown, Sontag looks seductively into the camera, straight at her lover. One of her bare legs is exposed, splayed out from beneath the sheets.

Williams brought it up to Meriwether during one of their first conversations. “She’s sick and she’s in a hospital bed, but she’s being photographed by the person she adores and who adores her. And her leg is coming out of the sheets. There’s gorgeous provocation, and there’s so much love and lust in her eyes. She looks so sexy and in love,” Williams says. “It has stayed with me for years, and I thought of it again in the context of this show. Because Molly has to radically accept her body and all of its failings, against her wishes, she’s able to radically accept what bodies do with people’s wishes. That was a beautiful transmission.”

Meriwether says the portrait ended up being a North Star for the show, specifically the idea that “a sick body can be a sexual body.” She wrote the episodes about Molly’s death while thinking of the photograph. Williams didn’t let it go, either. On set, as she prepared to film the death, she stuck her leg out of the hospital sheets and asked Meriwether, “Are we getting the leg?” Meriwether was stunned. “To be in the midst of all that, to have the frame of mind to be in the character, but also being outside of it,” she says. “It’s real good shit.”

Sitting in the restaurant, Williams tries to explain what the death scene felt like, taking long pauses and occasionally addressing herself. First she explains how Molly’s bravery — the way she accepted and directed the tone and nature of her life and death — reminded her of the very first time she felt proud and in control of her body: when she gave birth to Matilda at 25. “I was allowed to labor for 24 hours without any intervention and without any monitoring. And I had said at the outset that this is what I wanted,” she says. “And my care provider took that at face value and helped give me the experience that I had told her was important to me.”

She and her doctor stuck with the natural-birth plan even as she admitted to feeling a nine out of ten on the pain scale. “That experience for me at that age, of seeing that my body was capable of doing something … How could I not love myself if I could make this experience happen? If I could make something so beautiful, so perfect, what could possibly be wrong with me?” she says. It permanently changed the way she saw herself. “In that moment, I was completely reborn.” That her doctor listened to her and allowed her to keep going even when she was in extreme pain — that she had the control — was equally powerful. “I carried that experience with me, being in charge,” Williams says. “I really liked being the boss.”

She later made the connection between her labor and the death scene. “Life and death are in the room at the same time, in the same place,” Williams says. “When you can give somebody the experience that they crave of their engineered exit, I related it to this experience that I had when I was 25 — of how this doctor cared for me and how much I appreciated her ability to allow me to feel.”

At the end of the day, which was also the end of the shoot, Williams stood up from the bed. She left the hospital soundstage and walked outside into the sunlight. “It’s not normal that we get to walk away from it,” she says of pretending to die and then rejoining the living. “It feels like the most jubilant experience that you could possibly imagine.” She began to run. “I remember how long my legs felt,” she says, smiling. “I felt like an antelope or something. Like I didn’t know my body could do this.”