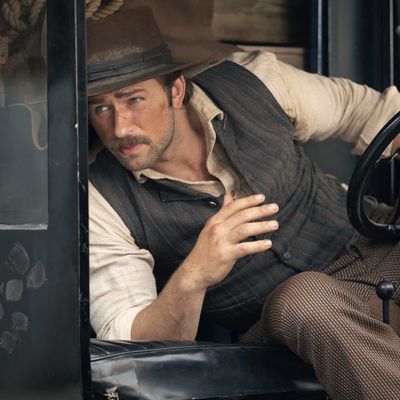

Photo: Lauren Smith/Paramount+

“Journey the Rivers of Iron” is an especially grisly episode of a series that’s never easy on the squeamish. Alex, the most delicate Dutton, is the victim of an aggravated assault. Zane has his head strapped to a block so a jittery doctor can peel back his scalp and drill through his skull. When Lizzie eventually asks for a needle to self-administer her rabies vaccine, I hardly flinched. I’d already seen too much, and yet I hadn’t seen the worst of it. Back in Bozeman, Lindy, one of Donald Whitfield’s sex workers–in–residence, strangles another sex worker that he was keeping as a pet.

Even watching through my fingers, it’s obvious that “Journey the Rivers of Iron” is the best episode of 1923’s second season so far. The Dutton family is diminished, but this week, on the eve of springtime, they’re finally recovering. We’re encouraged to believe that, come thaw, they might even be in a position to throw some punches of their own. Zane is on the mend, and Spencer is only two or three states from the ranch. Lizzie is pregnant, and Alex is en route. If they can just survive what’s left of this brutal winter, they might survive forever.

Of course, the Duttons’ greatest enemy — the world — is mounting another attack, refilling its coffers and amassing troops. Whitfield has a three-step plan for remaking Montana into a winter wonderland for the rich men who live along Chicago’s lakeshore and New Yorkers who mistake the Hudson Valley’s hills for real mountains. Step one: Develop the modern airliner. Step two: Pave a freeway through Paradise Valley at the government’s expense. Step three: Build a resort.

“Americans no longer rely upon their hands for money,” Whitfield explains to a room of nodding investors who are eager to see their lives in Bozeman as covetable. “They use their minds.” This might be the exact moment when this country lost its way, at least according to the laws of Yellowstone. Hands aren’t mere metonyms for the men they belong to; hands are the man. Only Banner Creighton sees the teeny-weeny problem with Whitfield’s proposal, and it’s not the bit about inventing safe and speedy air travel. To build a resort in Paradise Valley, you’ll have to bulldoze Jacob Dutton to the ground — to rip from his leathered hands not just his family’s parcel but their whole way of life.

Whitfield tells Banner to assemble an army of sheepherders who want the same land for grazing in summer, and Banner says he’ll ask the miners, too. On a map, Whitfield identifies an unincorporated part of the state where they can secretly dump the bodies of Dutton men who throw themselves between the ranch and the inevitable march of progress. But can it really be so simple? I’m struggling to believe Montana will ignore the murder of the livestock commissioner and his entire family just because the killers dug the perfect ditch. Or that the Scots will be content to graze their sheep on a ski resort in the low season.

Before he pledges his men to Whitfield, Banner talks it through with Ellie. His wife has remained impressively skeptical of the mining tycoon, but the promise of a future for her family is too much to resist. She wants her son to go to university; she wants her grandsons to inherit a good name. Ellie tells her husband that if he’s going to steal another man’s castle, he can’t leave the prince in any condition to take that castle back. I agree with her cool assessment, and yet you’d really have to squint to mistake Jake Dutton for a prince right now. It’s Whitfield that Banner needs to outwit. If you’re risking your life, do it to become king of the mountain, not prince of the valley.

Because, from what we’ve seen in 1923, being prince of the valley is punishing. Take today as an example. Jake Dutton spends the morning assisting on meatball brain surgery so gruesome that his nephew Jack nearly hurls on several occasions. The patient on the table is the Yellowstone ranch foreman, who only finds himself in this vulnerable position in the first place because powerful men want his boss’s land. Jake watches him wake up mid-surgery, in agony, with a shop-class hand drill burrowed into his head. Somehow, the surgery is successful, but that’s only Jacob Dutton’s morning. “One calamity down,” he says wryly.

In the afternoon, Jacob has to convince his nephew’s wife not to leave him, which is tricky to do because Jack’s fealty to his uncle’s ranch is the main problem in the marriage. I actually thought Jake handled Lizzie well by establishing a third option between staying at the Yellowstone and leaving it forever; Lizzie can just visit home for a bit and return when the mercury rises. We’ll never know if Jake’s plea would have been successful, though, because the doctor confirms that Lizzie is pregnant. That’s why she’s having such an adverse reaction to the rabies vaccine.

After that, Jacob heads to the porch to grab a few quiet minutes with his wife between debacles. They share cute, inexplicable banter about how he doesn’t understand women at all and that’s somehow the bedrock of their marriage. Aunt Cara was negging long before The Pick-Up Artist.

Then, for dinner at the end of a long day, Jake probably has some broth or leftover gruel and thinks about how cold his bones are. Maybe he ruminates on the lien on his house as Cara lies next to him. Or maybe it’s guilt that chases his sleep away. Look what happened to Zane. He feared he would never walk again after the beating he took, and now he’s itching to fight a land war for another man’s family. Maybe it would be better for everyone if Jake just walked away from the Yellowstone. Better for Zane and Alice, who could move to California, where mixed-race marriage is legal. Better for Jack and Lizzie, who could raise their baby in the relative warmth of Boston. Better for doc, who hasn’t been home since before the blizzard because the Duttons make so much trouble.

And all of this? This happened on a relatively quiet day for the aging prince of Paradise Valley.

Things didn’t go nearly so well for the Dutton diaspora beyond Montana state lines. After being robbed and beaten in Grand Central Station, Alex flings herself onto a moving train. She walks down the aisles of the first-class cabins with a black eye while the types of people she used to be friends with gawk. She hasn’t a penny left. The worse news is that she’s sharing a bunk with other people’s children, at least until Boston.

Spencer, meanwhile, continues his run of bad luck that momentarily disguises itself as good luck. For example, it almost seems like good luck when the Fort Worth sheriff offers him a ride to the train station, though it’s quickly revealed to be bad luck when he’s told to sit in the back seat like a perp. (Personally, I was surprised to learn Luca is such a squawker. Wasn’t he raised on omertà?)

It also seems like good luck when the sheriff offers to set Spencer free in exchange for making the booze delivery he had already promised to make, though it’s bad luck when the sheriff later handcuffs him to the steering wheel. (Here, I was confused as to why the police didn’t orchestrate a proper sting operation once Spencer gave them the delivery address. Why just bust down the door with no plan?)

Still, it’s good luck that the sheriff leaves the key in the ignition and that Spencer is able to work himself free. And it’s good luck that the Temperance Society is forcing a tarred prostitute to parade down Main Street at the exact moment Spencer goes on the run because (1) it creates an obstacle for the pursuing sheriff, and (2) it lets Spencer free a prostitute on his way home. You can take a man’s ranch, but not his savior complex. It’s good luck to hop on a train headed west and bad luck to find the car already occupied by hobos that will require killing.

Ultimately, Spencer ends the episode where he started it: walking north from Fort Worth headed home to a place that won’t be home when he arrives. Because there aren’t roads in the Montana that Spencer is from. There’s no river of iron to drop his wife at a nearby station. Just wait until Spencer hears about the ski resort, and the freeway, and the airplanes. About the lien on the land that’s belonged to his family since before Montana was a state.

Teonna, Pete, and Runs His Horse are still in Texas, too. They’re helping ranch hands drive cattle in the only 1923 story line that has any joy or vibrancy to it. It’s not a coincidence that God’s golden light shines brightest on the land in which men are still making their money with their hands. I’ve never seen Texas look prettier than it does when Taylor Sheridan shoots it. But soon, I worry, there won’t be any Texas in Texas either. The fairgrounds where the cowboys stop for lunch are plastered with Wanted posters bearing a sketch of Teonna. America is coming for her, like it came for Paradise Valley.

It’s the cycles of feast and famine that make life on the range so hard and so fulfilling we’re told over and over again across Yellowstone and its spinoffs. In 1923, though, it seems like it’s always famine, and famine’s less fun to watch. This week’s episode offered us longer days and brighter evenings — the promise of story lines reaching fruition. That Spencer will make it home again; that Teonna will cross over into Mexico and find freedom; that Jack and Lizzie will have a baby. Frustratingly, it also warns us against the same longing it conjures. “Spring teases the senses with warm mornings and green buds of new grass and the hope of summer’s bounty,” Elsa Dutton tells us from beyond time, where the Dutton family story is already over or maybe never-ending.

“Then blankets that hope in snow.”