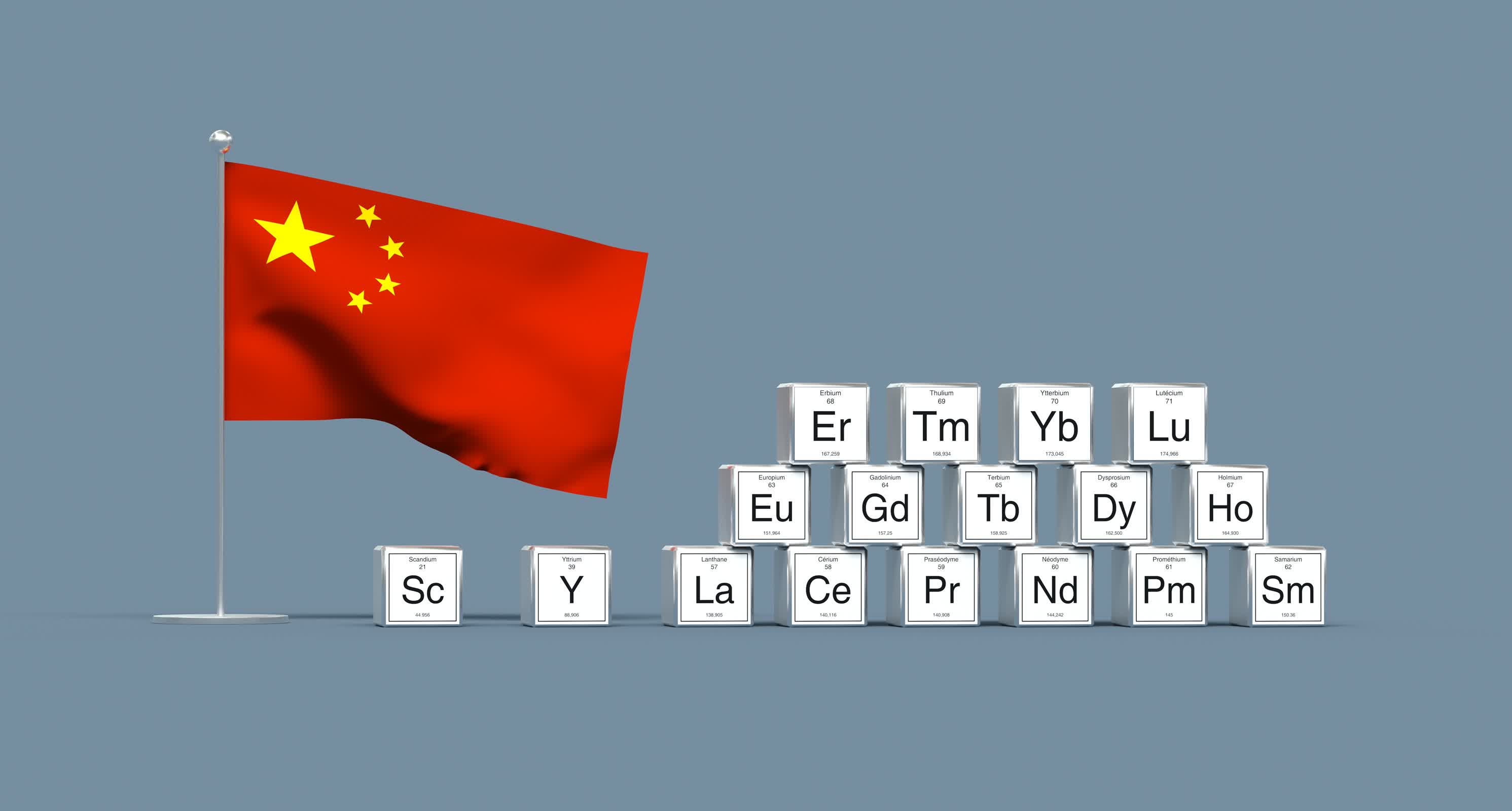

China has tightened control over the global rare earth supply by introducing new export restrictions that could disrupt industries dependent on these materials. The latest measures, announced late last week, target seven elements – including scandium and dysprosium – used in smartphones, electric vehicles, and military tech. Rather than a blanket ban, the rules require exporters to obtain licenses and specify how buyers intend to use the materials, creating bureaucratic friction that could delay shipments and drive up costs.

Rare earth minerals play a critical role in modern technology thanks to their unique chemical and physical properties. Scandium, for instance, enables high-performance RF front-end modules in telecom devices by forming Scandium Aluminum Nitride, which boosts signal strength and efficiency. Manufacturers use this material in high-frequency wave filters for 5G smartphones, Wi-Fi systems, and base stations. Although each semiconductor wafer requires only a small amount of scandium, leaving it out would compromise the performance of critical telecom components.

Dysprosium supports a wide range of industries. Manufacturers add it to neodymium-iron-boron magnets in hard disk drives and electric vehicle motors to stabilize magnetic properties at high temperatures. Engineers also use dysprosium for radiation shielding in nuclear reactors and satellites. Its use in Magnetoresistive Random Access Memory (MRAM) strengthens stability in the device’s magnetic layers.

Other restricted elements – including gadolinium, terbium, yttrium, lutetium, and samarium – also serve critical functions across advanced technologies. Substituting them often requires expensive workarounds or leads to noticeable performance losses, making them difficult to replace without compromise.

China’s dominance in rare earth production stems from decades of investment in mining, refining, and processing infrastructure. The country produces nearly 70 percent of the world’s rare earth mining output and over 85 percent of refined production. Although rare earths are not geologically scarce, their extraction and refinement are complex and expensive. China’s ability to efficiently produce these materials has allowed it to maintain a near-monopoly on supply chains essential to industries from consumer electronics to defense systems.

The export restrictions seem to be a strategic response to rising trade tensions with the United States. Beijing has presented these measures as necessary for protecting national security, citing tariffs imposed during the Trump administration. However, they also function as a geopolitical lever to influence global technology markets. These new restrictions represent the third round of export controls China has enacted recently, following earlier limitations on key materials like gallium and germanium used in semiconductor manufacturing.

The restrictions could have profound implications for chipmakers like Broadcom, Qualcomm, TSMC, Samsung, Seagate, and Western Digital. Rare earths play a critical role at various stages of semiconductor production, from wafer-level materials to high-performance components. Supply disruptions could send ripples through supply chains strained by ongoing global chip shortages. Analysts warn that prices for restricted materials may double or even quintuple as manufacturers scramble to secure alternative sources.

China’s export controls have far-reaching consequences, impacting commercial markets and national security. Rare earths are vital for advanced defense systems, from fighter jets and guided missiles to surveillance drones. If supply disruptions persist, they could delay key military projects or drive up costs significantly. The U.S. remains highly dependent on Chinese imports for these materials, with only one domestic mine, a vulnerability that policymakers have flagged as a serious strategic risk.

Despite China’s dominance, efforts to diversify rare earth supply chains are underway globally. Countries like Australia and Vietnam have expanded production, while others focus on developing recycling technologies and alternative materials. Japan, for instance, has decreased its reliance on Chinese rare earths from 90 percent to 60 percent by opening domestic mines and forming partnerships with suppliers like Australia’s Lynas Corporation. However, Beijing’s control over these materials remains unrivaled for the most part.